[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

BACKUP Newsletters 2007

.................................. December 2007

33 Stone Kannon Statues of Hakodate

Ukimido, the floating hall and Matsuo Basho 浮御堂

Narita Train Line Special Service 川崎大師への初詣に

Osaka '70 World Fair - Ōsaka Banpaku (大阪万博) Memorial Dolls

Nakano Clay Dolls 中野土人形

Nachi Black Stone Carvings ... 那智黒のだるま

Doraemon Daruma Dolls (ドラえもん)

Kiyomizu Small Clay Dolls 清水豆人形(京都府)

Kyoto Clay Dolls 京土人形

Dogo : Hime Kitty Daruma, Princess Daruma from Dogo Onsen Matsuyama ひめだるまキティ, 姫だるまキティ

http://darumamuseum.blogspot.com/2007/04/mickey-mouse-disney.html

Kodaruma BLOG Collection of Kodaruma San

Kohi Kappu 呉須だるまコーヒー碗皿 Coffee Cup with gosu blue glazing

Orchid "Purple Rain" Daruma

Raku Kichizaemon XV 樂 吉左衛門 Potter of the Raku tradition

Maruyama Okyo Maruyama Ōkyo (1733–1795; 円山 応挙) Painter

Exhibitions in Winter 2007

French Magazine "Daruma"

Wakamiya Hachimangu Mie Papermache Lucky Daruma . 若宮八幡宮の福達磨」(三重)

.................................. November 2007

Naito Meisetsu 内藤鳴雪 Haiku Poet. 1847 - 1926

Korean Ambassadors to Edo Choosen Tsuushin Shi .. 朝鮮通信使

Big Spenders, the 18 Playboys of Edo (juuhachi daitsuu) 十八大通

Kano Eitoku 狩野 永徳(1543 - 1590)

.................................. October 2007

Nio, Deva Kings 仁王 (Nioo, Niou)

Inkan, Hanko 印鑑、判子 <>Personal Name Stamps and Seals

H A I K U about Fudo Myo-O

Bunchin 文鎮 ... paperweight

Park, Kume Island Daruma Park .. 久米島 だるま山公園 Okinawa

Takasaki Town Mascot ... 高崎だるま "たか丸"

TSUBA, 鍔 つば the sword guard some additions

Kitagawa Utamaro 喜多川歌麿(1753~1806年)

Meditation, Skillful Meditation

Objects with Daruma ダルマオブジェ. Ishii Tatsuya

Okimono ... Statues with Daruma 置物

Restaurant "Daruma San Ichome" だるまさん一丁目

Obidome ... Belt Buckle 帯留

Garuda Halo of Fudo Myo-O karura-en 迦楼羅焔(かるらえん)

Kannabi, a place of the Gods 神奈備

Fujisan Mt. Fuji 富士山

Gyoran Kannon, Kannon with Fish Basket, 魚籃観音(ぎょらんかんのん)

Katoo (gatoo) Pottery Lamp 瓦燈

Kintaroo, Strong Boy Daruma だるま抱き金太郎

Maekake ... Apron 前掛け

.................................. August 2007

Nishimura Kocho (Nishimura Koochoo) 西村公朝 Master Carver

Renkoo-In, Renkoin 蓮光院初馬寺 Tsu Town

Temple Ishiyamadera / 石山寺

Ikkanbari ... 一閑張・姫だるま Princess Daruma Dolls from special papermachee, Ikkan type

Women's slope (onna-zaka)/ Men's slope (otoko-zaka) 女坂 . 男坂

Jeans, Daruma handpainted on denim material

Nuigurumi ... ぬいぐるみ Stuffed dolls

.................................. July 2007

Hime Daruma 姫だるま Princess Daruma, Introduction

Seals ... シール

Onomichi, a coastal town 尾道

McFarland, Yoshiko McFarland Artist

Kushi 櫛 (くし) Comb

Kin 18金製 18 Carat Gold Daruma

Kanemochi 金持ち(餅)だるま Rich Man Daruma (Rice Dumplings)

Hirame ひらめ 平目と魚 Flounder and other fish

Cartoons with Daruma

Calligraphy , shodoo 書道

Maso Bosatsu, Senrigan and Junpuji 媽祖菩薩, 千里眼, 順風耳

Kurama Stone, Kurama Ishi 鞍馬石

Grapes Yakushi, Budoo Yakushi 葡萄薬師

.................................. June 2007

Yen Eyes, Dollar Eyes Papermachee Daruma Dolls

Tanuki 狸 ... A Badger posing as Daruma ... and the Tanuki Scrotum, kintama 金玉

Shanghai Fine Jewellery and Art Fair ... SFJAF

Mouse, Computer Mouse and remocon devices ダルマウス

Design, Japanese Design and Daruma

Natto 納豆 ... Fermented Beans

Fabrics, Cloth 布、切れ

Kaeru 蛙 かえる ... The FROG

Fudo Shin, The Immovable Spirit 不動の心

Glass ガラス Tsugaru Glass, Tsugaru Bidoro 津軽びいどろ 瑠璃だるま

Migawari Fudo, the Substitute Fudo みがわり不動、身代わり不動尊

PEACE and Daruma

Color Symbol Daruma カラーだるま

Chrysanthemum . 達磨菊(ダルマギク) . Darumagiku

Gojinjoo Taikoo 御陣乗太鼓面 Drummer Masks

I LOVE DARUMA .. various goods

Kawasaki Kyosen 川崎巨泉(1877-1942) ... 5000 Sketches of Japanese Folk Art

Kawa zaiku 皮細工 Leather Goods : Notebook cover ノートカバー(達磨カービング) notebook cover / Holder for business cards 名刺入れ meishi ire

Koozen-Ji 興禅寺 Daruma Temple Kozen-Ji White Daruma Statue

Noomen 能面 達磨 Noh Mask More about the Noh Theater

Shinsengumi 新選組だるま Papermachee Doll for the Samurai Group "Shinsengumi"

Shita 舌 Daruma sticking out his tounge !

Table, Dharma Table Design

Tibet チベット <> Padama Sangye: The Daruma Connection .. and .. Tibetan Daruma Doll

White Daruma Goods Wedding Daruma 婚礼だるま konrei Daruma and more

Yuzen (yuuzen) und Chiyogami ... 友禅 / 千代紙 Papercraft with Washi Japanese Paper

Yakkyuu 野球 Baseball goods with Daruma

Japanese Prints, Store by Anders Rikardson

Remote Control ... だるまリモコン

Kannon Daruma, Daruma Kannon だるま観音

Acupuncture ... 針灸

Cap Clip だるま キャップクリップマーカー

Chigiri-e .. ちぎり絵 Paintings from torn paper

Iyashi no daruma 癒しのだるま ... Healing Daruma, various forms

Hashi oki ... chopstick rests 箸置き

Maruishi Kaku, a papercraft artist . 円石格

Mimi, Daruma with Ears 達磨の耳 だるまの耳

Mayu Daruma from silk cocoons . 繭だるま / まゆだるま / 繭達磨

Onishi Clay Dolls 尾西のだるま / Okoshi Tsuchi ningyo 起の土人形

Tissue Paper Box チッシュペーパーボックス

Wagashi 和菓子 . Japanese Sweets

Mii-Dera, Mii Temple 三井寺

.................................. May 2007

. . . !!! . . . Latest in the new ARCHIVES

Tairyuu-Ji, Big Dragon Temple 太龍寺

Tofukuji Temple (toofukuji 東福寺) and master gardener Shigemori Mirei 重森三玲

Demukae Fudo Son.出迎え不動明王

E ... 絵 ... Paintings of Daruma

Happuu Fudoo . 八風吹不動

Hoki Bosatsu, Hooki Bosatsu 法起菩薩 ... "Hoodoo Sennin" 法道仙人, Temple Bodaiji 菩提寺, Saint Tokudo 徳道上人

. Maekawa Senpan 前川千帆 . Woodblockprints

A living Daruma, Ono Katsuhiko 大野勝彦

Hell Concepts in Daoism 道教と地獄

Fudoosan <> Real Estate Agents 不動産

Daruma Fudo Doll and Fudo Daruma paintings 達磨不動明王, 不動達磨図

Greeting Cards with DaMo

Hashi, O-Hashi ... Chopsticks お箸 おはし

Hanger for small thingsハンガー

Helmet for motorbikes ヘルメット

Kootsuu anzen (kotsu anzen) ... traffic safety, road safety 交通安全だるま

Mudra, Daruma Mudra meditation position dharma-cakra-pravartana

Nagoya Obi ... Sash from Nagoya with embroiderie. 名古屋帯

Taka ... Hawk Daruma Doll 鷹だるま

Nyoi Hooju, Wishfulfilling Jewel 如意宝珠, mani hooju 摩尼宝珠

Nyoirin Kannon, Wishfulfilling Kannon如意輪観音

..... Seiryuu Gongen, Dragon Deity Zennyo 清瀧権現

Yonaki Jizo and babies crying at night 夜泣き地蔵

History of Buddha Statues in Japan Deutsch

Shikishi <> 色紙 Decoration Art Board

Shoki (Shooki 鍾馗 しょうき)The Demon Queller

Snacks with Daruma スナック Food

Dog <> 犬

Fire <>火達磨、火だるま

Kaminari Chan ... Little Thunder and Little Daruma

Soccer World Cup <> サッカー ワールドカップ

Otoshi, Daruma Otoshi だるま落とし だるまおとし

Kusuri, kusuribukuro 薬袋 Medicine Bags

Milk Cartons 牛乳パック

Japonism and Daruma

Stamps, rubber stamps

Shoogatsu ... 正月 New Year Decorations

Deutsche Daruma Informationen Deutschland

Uba Gongen 姥権現 ... at Mt. Iidesan 飯豊山. Uba Jizo 姥地蔵.

Mountain hermits, sennin 仙人

..... Three Hermits: plum, chrysanthemum and narcissus

Ajimi Jizo 嘗試地蔵 and Kobo DaishiKoya san

Winnie the Pooh プーさん, プー小熊

.................................. April 2007

Kubizuka, mounds for a severed head 首塚

Inuki Fudo in Tochigi 居貫不動 with many scriptures inside

Yugasan Fudo 由加山厄除不動

Tainai Butsu 胎内佛, 胎内仏Small Statues inside a statue.

..... offerings inside a statue, zoonai noonyuuhin 像内納入品

Making Buddha Statues 仏像作りBasic Information

Tea scoop <> Chami with Daruma Carving 茶箕(ちゃみ)

Cup soup カップラーメン

Piggy Bank (chokin bako 貯金箱)

Strap (ストラップ)

Mickey Mouse Disney and Daruma

Victory Daruma, Examination Daruma / Gookaku Daruma 合格だるま

Onsen Daruma Yu 達磨湯, だるま湯 <> Hot Springs named DARUMA

Kotahouse Daruma Store

Animation アニメ

Haizara 灰皿 <> Ashtray

Kashi bin 菓子ビン <> Glass for cookies

Taihoo Daruma, the big cannon <> 大砲だるま

Jundei Kannon, Juntei Kannon 准胝 観音 Mother of all Buddhas, 准胝仏母(じゅんていぶっぽ)

Seated Fudo Myo-O Rietberg Museum, Zurich

Bishamonten Festival and Daruma Market

Daruma Clock だるま時計

Daruma Stove だるまストーブ

(ゲゲゲの鬼太郎, Ge Ge Ge no Kitarō)

Edo Patterns, share 洒落 Kamawanu, Kikugoro goshi and other puns

Nagaya だるま長屋殺人事件 Row houses in Edo

Kazusa Daruma 下総だるまPapermachee Dolls (see also: Kashiwa Daruma)

Sakushu Kaido, The Old Road of Sakushu 作州街道 With many details on the way !

Kita no Sho Shrine

Izumo Kaido, The Old Road of Izumo 出雲街道 With many details on the way !

Dragon Shopsign, Tsuboi Town

Shugendo: "The Way of the Yamabushi" by Erik Krautbauer

O-Shichi Kannon お七観音 Temple Tanjo-Ji Okayama

Ito 京美糸 <> Silk thread for sewing

Tanabata Daruma 七夕だるま Hiratsuka

.................................. March 2007

Seven Gods of Good Luck as Daruma Dolls 七福神だるま

The Gods of Japan and Haiku (Kami to Hotoke)

Guinomi ぐい飲み Cups, Teacups

Tairyoobata (tairyobata, tairyooki) 大量旗 Ships Flagsfor a bountiful catch

Coca Cola Items and Daruma Advertisement

"Dragon wheel, dragon vehicle" ryuusha 竜車, 竜舎Part of a Pagoda Final Decoration

Walnut (kurumi 胡桃)

Kanji Character AI looking like Daruma漢字のだるま絵

Tiles, Roof Tiles Kawara 瓦 かわら. onigawara 鬼瓦

Hitokotonushi 一言主 "God of One Word" at Katsuragi Mountain, 葛城山の一言主神社

TEE shirts

Telephonecards and Hajima Daruma Market 拝島大師だるま市

Ticket for a bus ride to Takatoo Daruma Market 高遠のだるま市

Darumagama, a kiln in Bizen Tokian 陶器庵 備前焼き

.................................. February 2007

Shiromen Fudo no Taki, a Waterfall

Pilgrimage to 18 Shingon Temples

Kashigata 菓子型 Cake mold of iron

Coasters

Bon, 盆 a tray

Shunga Daruma 春画だるま Erotic Pose

Sekiri 隻履達磨Daruma carrying one sandal

Robot Dolls ロボコンだるま

Plates with Daruma Design お皿

Mascott Hot Pepper

Tenugui 手ぬぐい Small Hand Towels

Toothpick holder

ゴルフバグ Golf Bag

Gin 銀 Silver Daruma

Designer Daruma by Debi Bender

Fukuyama Bingo Shrine 福山: 備後護国神社

..... with Daruma Votive Tablets (ema)

Anko Daruma of sweet bean paste 餡子だるま , だるまあん

.................................. January 2007

Signboard for Coca Cola

Inoshishi : Papermachee Doll of a Wild Boar for 2007

Card from TV GUIDE magazine

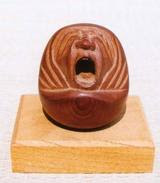

Stone carving small okimono

Keyholder with Kyupi Daruma Doll

Lighter from ZIPPO

Hamburger wrapper Examination Food

Juken Food 受験フーズ Examination Hell Food, January 2007

Kitsune Daruma, Fox Daruma 狐だるま 狐達磨 From Shibata Town, Niigata.

Pinoccio Daruma ピノッキオ だるま 。。。!!!

Strap with Winebottle. From Carlo Rossi Vinyard, 2006. ..オリジナル ミニだるまストラップ

Salt and Pepper Shaker

Tsumayooji (tsumajoji) 爪楊枝 つまようじ <> Toothpick-holder

Metal Hibachi Brazier

Rope-jumping plastic doll

Train Ticket from Gujoo Hachiman Daruma Market Promotion

Quotes from Bodhidaruma Quotes of Bodhidaruma

CE Mark Daruma for Europa

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

ALL ... Latest Additions from 2006

..... Latest Additions from 2005 are here:

http://darumasan.blogspot.com/2005/12/2005-latest-additions.html

**********************

Please send your contributions to Gabi Greve

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Darumasan-Japan/

To the Daruma Museum ABC Index

http://darumasan.blogspot.com/

World Kigo Database

Daruma Museum Waitinglist

. . . . . . . . . . . .Daruma Museum Archives since 2007

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Showing posts sorted by date for query festival. Sort by relevance Show all posts

Showing posts sorted by date for query festival. Sort by relevance Show all posts

12/14/2013

1/03/2011

Kamon family crest

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Family Crest 家紋 kamon

Familienwappen

© PHOTO : yotchan

This is a

. Daruma from Shirakawa 白川だるま

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Mon (紋), also monshō (紋章) Monsho,

mondokoro (紋所), and kamon (家紋),

are Japanese emblems used to decorate and identify an individual or family. While mon is an encompassing term that may refer to any such device, kamon and mondokoro refer specifically to emblems used to identify a family.

The devices are similar to the badges and coats of arms in European heraldic tradition, which likewise are used to identify individuals and families. Mon are often referred to as crests in Western literature, which is another European heraldic device that approximates the mon in function.

On the battlefield, mon served as army standards, even though this usage was not universal and uniquely designed army standards were just as common as mon-based standards.

Check a long list of famous Japanese crests!

© More in the WIKIPEDIA !

.................................................................................

montsuki 紋付 formal wear with the family crest

CLICK for more photos !

monuwaeshi, mon uwa eshi 紋上絵師 painting family crests

The space for a family crest was usually left white by the cloth dyer and a special painter added the pattern and colors.

Since crests had become quite popular with the townspeople of Edo, they were used not only for official robes but also for decorations of every-day things, even 手ぬぐい tenugui hand towels.

The workshop of a crest painter did not take up much space and could be done in a small home in Edo.

- quote -

There are different styles of mon too. In the picture below, showing three variations of icho (ginko) mon, you can see three versions of a the mon: hinata – full sun (left), kage – shadow (middle), and nakakage – mid shadow (right). The more subtle versions are for slightly less formal occasions. There are also embroidered mon, called nui mon.

hinata mon 日向紋 - - - kage mon 陰紋 - - - nakakage mon 中陰紋

A family may choose a mon that is associated with their family (a family mon is called a kamon) or just opt for one they like instead. They are seen on all sorts of items in Japan: clothing, signs, boxes, ceramics, banners etc.

- source : wafuku.wordpress.com -

上絵の道具 tools of a crest painter

家紋を描くときに使う上絵道具の一部

(左から)from left to right

①分廻し(一本)bunmawashi compass to make a circle

②上絵筆(一本) ③定規 ④丸棒(二本) ⑤小刀(一本)

⑥丸刀(大、小) ⑦摺り込み刷毛(大,中、小) ⑧平刷毛(大、小)

⑨つや刷毛(大、中) ⑩平ゴテ ⑪丸ゴテ ⑫押さえゴテ

- Look at more photos how the tools are used:

- reference source : homepage2.nifty.com/montake/dougu -

「各種紋入れ加工」

「紋直し mon naoshi」「紋入れ・入れ紋 mon ire」「抜き紋 nuki mon」

「摺り込み紋 surikomi mon」「切り付け紋 kiritsuke mon 」

「のり落とし上絵 nori-otoshi uwa-e」「加賀紋 kaga mon」

(Kaga mon is a crest for a "fashionable person" and was very colorful, sometimes with embroidery.)

- with detailed descriptions

- reference source : homepage2.nifty.com/montake/eigyo -

- Check out the detailed page of 紋章上絵師

Itoo 伊藤武雄 Ito Takeo

- reference source : homepage2.nifty.com/montake/mon -

.......................................................................

. Edo craftsmen 江戸の職人 .

mongata shi 紋形師 craftsman making Mon patterns

source : edoichiba.jp.. mongata...

.......................................................................

- quote -

Family-crest master fears he’s one of a dying breed

- Tomoko Ontake - Japan Times -

Dressed in a black kimono and wearing a pair of eye-catching black, triple-framed spectacles, Shoryu Hatoba straightens his back as he sits on the tatami floor of his quaint studio in Ueno, central Tokyo, holding a pair of bamboo compasses fitted with a brush dipped in ink in place of a pencil.

- snip -

But 56-year-old Hatoba is now one of a dying breed of monshō uwae shi (family-crest painters and designers). “I’m an endangered species,” the Tokyo native concedes.

That’s because Japan is now on the verge of losing the tradition of making and preserving the ritual or everyday use of kamon (family crests) — which pretty much everyone in the nation once had. That’s despite the fact that its first known family crests date from the eighth century, when nobles at the Imperial court, and then samurai warriors, started using them as badges of identity or ownership.

But unlike in the West, where family crests were exclusively for the nobility, in Japan their adoption grew exponentially during the Edo Period (1603-1867), and especially during its economically and culturally vibrant golden age known as the Genroku era (1688-1704), Hatoba explains.

Then everyone, but men mostly, started featuring them in whatever design they liked on their kimono. That even included commoners — who mostly had no family names at all until a law in the modernizing Meiji Era (1868-1912) required everyone to have one — though Hatoba says women were generally late to the kamon party, only adopting them at the end of the Edo Period.

- snip -

The crests’ motifs are derived from a wide range of plants, birds and other animals.

- snip -

As a profession, monshō uwae shi demands microscopic attention to detail and command of many sophisticated techniques — not to mention aesthetic sensibilities. And, as Hatoba explains, a crest’s component parts all have to be rendered in a circular design on average only 38 mm in diameter for men’s kimono, and 21 mm for women’s. Interestingly, too, the number of crests on a kimono ranges from one to five — with more crests reflecting an occasion’s greater formality.

Hatoba, who apprenticed under a kamon craftsman for five years before opening his shop, is determined to keep the tradition alive. To do that, he has collaborated with creators and corporations in various genres, featuring kamon designs on everything from bags to boxes of wagashi (traditional Japanese) sweets.

- snip -

- source : Japan Times 2013 -

. Edo shokunin 江戸の職人 Edo craftsmen .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Some crests covered in the Daruma Museum

. Mitsuba Aoi 三つ葉葵 Hollycock of Tokugawa Clan

. Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康

. Tokugawa Mitsukuni 徳川 光圀

The famous inro box with the "mondokoro" from Mito Komon.

.................................................................................

. Asa no ha 麻の葉の家紋 Hemp leaf

. Kuyoo no mon, 九曜の紋

Nine planets, nine deities representing the stars

. Myooga 茗荷 Japanese Ginger

. Rindoo no mon 竜胆 gentian blossoms

. Rokumon sen 六文銭 Six coins of Sanada

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Daruma in a turtle shell crest

亀甲に達磨

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

More than 90 Crests from shrines and temples

shinmon 神紋 Shrine crest - jimon 寺紋 Temple crest

京都嵯峨清涼寺

source : secure.ne.jp/~x181007/kamon

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

- quote

A tomoe (巴), also 鞆絵, and tomowe (ともゑ) in its archaic form, is a Japanese abstract shape described as a swirl that resembles a comma or the usual form of a magatama. The origin of tomoe is uncertain. Some think that it originally meant tomoe (鞆絵), or drawings on tomo (鞆), a round arm protector used by an archer, whereas others see tomoe as stylized magatama.

It is a common design element in Japanese family emblems (家紋 kamon) and corporate logos, particularly in triplicate whorls known as mitsudomoe (三つ巴).

A mitsudomoe design on a taiko drum (note the negative space in the center forms a triskelion)

Some view the mitsudomoe as representative of the threefold division (Man, Earth, and Sky) at the heart of the Shinto religion. Originally, it was associated with the Shinto war deity Hachiman, and through that was adopted by the samurai as their traditional symbol. One mitsudomoe variant, the Hidari Gomon, is the traditional symbol of Okinawa.

The Koyasan Shingon sect of Buddhism uses the Hidari Gomon as a visual representation of the cycle of life.

© More in the WIKIPEDIA !

. Hachiman Shrines in the Edo period .

- quote

Okinawan Symbols and History of the Hidari-Gomon

The Hidari Gomon and it was once the Royal crest of Ryukyu Kingdom in Okinawa. In Japanese it is called the Hidari mitsudomoe and is a common design element in Japanese family emblems (家紋) and corporate logos. The Hidari Gonon is the primary traditional symbol of Okinawa. It is unclear who used the symbol first but it has special significance to the Okinawan people especially those practicing the ancient art of Okinawan Karate. I have heard a couple different interpretations of the meaning of the symbol so their may be more than one definition for the symbol.

The Koyasan Shingon sect of Buddhism which came from China to Japan uses the Hidari Gomon as a visual representation of the cycle of life. Others believe that the symbol is Shinto related because in Shinto mythology the symbol is often used to signify the structure taking place between three worlds. Such worlds include heaven, Earth, and the Underworld.

One explanation that was particularly interesting to me was the Okinawan folktale where they interpret the "Hidari Gomon" as representing loyalty, heroism, and altruism to a proud island people and their descendants. They believe it to be expressed through a past full of struggle and hardship, but also a willingness to face the difficulties the ahead no matter what the cost.

snip

Later, back in the Ryukyu Kingdom, the envoy described the death of three warriors to the King. The King after hearing the story of the Ryukyu guards deaths had up the Hidari-Gomon drawn up to symbolize their heroic action. The symbol is said to portray the three Ryukyu warriors spinning around in the pot giving their lives for the greater good of the people. The symbol has since become the symbol of the Ryukyu Kingdom, a symbol which can now be found just about everywhere in Okinawa.

Many Karate dojos have also incorporated its use into the symbols they use to represent their particular style of the ancient Okinawan art of Karate

- source : chicagookinawakenjinkai.blogspot.jp

.......................................................................

- quote -

tomoemon 巴文

1 - Also tomoe 巴. A pattern of one or more curled tadpole shapes inside a circle. The pattern is also called right tomoe, migidomoe 右巴, or left tomoe, hidaridomoe 左巴, depending on the direction in which the pattern curves. When the comma shapes are placed in opposite directions, the term kaeruko domoe 蛙子巴 is used. The expressions double tomoe, futatsudomoe 二つ巴, or triple tomoe, mitsudomoe 三つ巴 are used depending on the number of tadpole shapes used.

The pattern was used to decorate the eave-end semi-cylindrical tiles *nokidomoegawara 軒巴瓦, *nokimarugawara 軒丸瓦 on Buddhist temples.

The pattern first appeared in the Heian period and has continued to be popular to the present day. Sharp pointed tomoemon forms in the Heian period gradually changed to short rounded forms by the Edo period. The same is design is also found on roof-tiles in China, where the tomoemon is associated with water. Therefore, the tiles are believed to ward off fire. A tile with this design is known as *tomoegawara 巴瓦 or *hanamarugawara 端丸瓦.

2 -

A design pattern comprised of one or more spherical head-like shapes each with a connected curving tail-like shape which ends in a point. The character tomoe 巴 means eddy or whirlpool; however, it is not clear if this was the original idea of the design. Some scholars are convinced that it stems from the design on leather guard worn by ancient archers-tomo 鞆 thus tomo-e 鞆絵, a tomo picture.

Others say it was originally a representation of a coiled snake. It may be the oldest design in Japan, because it is similar in shape to the *magatama 曲玉 jewelry beads of the Yayoi period. It appears as a design on the wall paintings of the Byoudouin *Hououdou 平等院鳳凰堂 (1053) in Kyoto, and in the Illustrated Handscroll of the Tale of Genji Genji monogatari emaki 源氏物語絵巻 (early 12c). It was widely used from the Kamakura period onward and is often found on utensils, roof tiles and family and shrine heraldry. Its frequent appearance in connection with Shinto shrines indicates that it was thought to express the spirit of the gods. Patterns of one, two and three tomoe exist, some facing left, others right.

- source : JAANUS -

.......................................................................

kite with a tomoe 巴(ともえ)Tomoe pattern

. 静岡の凧 Kites from Shizuoka .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

CLICK for more photos !

kani botan, kani-botan 蟹牡丹 crab and peony

A crest where the blossoms and leaves of a peony are formed in a way to represent a crab.

It was often used for cloths and carpets.

. Kani Yakushi 蟹薬師 "Crab Yakushi" Temple .

Ochiai, Gifu

Sendai Botan 蟹牡丹(仙台牡丹)- Date clan

牡丹紋は延宝8年(1680)20世綱村が近衛家ら拝領、21世吉村は手を加えて蟹牡丹(仙台牡丹)としている。

鍋島緞通 carpet from Nabeshima

蟹牡丹唐草文 kani botan karakusa mon

Carpet with kani botan pattern.

- source : bunka.nii.ac.jp/heritages -

. karakusa 唐草 / からくさ Karakusa art motives .

karakusa moyoo 唐草模様 Karakusa pattern. Karakusa arabesque

Chinesischen Arabesken und Rankenornamente

.......................................................................

source : cocomiura3.cocolog-nifty.com

色絵牡丹文変形皿 kanibotan pattern - Nabeshima

鍋島

左右の葉が中央の牡丹の花を抱き込むように描かれています

蟹の姿を思わせるので”蟹牡丹”と呼ばれるそうです

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

. Legends and Tales from Japan 伝説 - Introduction .

kamon 家紋 family crest

If people fought about the parents of a child, in former times, they used to wash the 胞衣placenta in water and when it floated up, the proper Kamon would show.

.......................................................................

愛知県 Aichi 岩倉町 Iwakura

daija 大蛇 big serpent

じいさんが神社の裏を通りかかったとき、大蛇が這っていくのにでくわした。鳥肌が立って、3年間はこのことを口外しないので行ってくれと言うと、大蛇は去った。その大蛇は尾が切れていて、先のところに丸に太いと書いた文字がついていた。その字は神明様の御神紋だったので、大蛇は神明様のお使いと分かった。

.......................................................................

青森県 Aomori 大間町 Oma

hotoke no zaisho ホトケの罪障 Buddhist attonement for sins

Once a man about 38 years of age came to the temple asking what to do. He felt very weak and could not go to work any more. After some explanation this became clear:

In former times at this fisherman's home a dead body got caught in the net. The family had taken care of it in a funeral, but since the family crest was different, the man's sould could not go to the Buddhist paradise. So they performed a special ritual and he was healed.

.......................................................................

愛媛県 Ehime 成妙村 Narutaemura

shirohebi 白蛇 white serpent

昔、太宰家で紋付を出そうとしたが、櫃がどうしても開かない。櫃を叩き壊すと白蛇がいたので殺した。それからは、生まれる子みなに三つ鱗がついていた。太夫さんに祈祷してもらい怪異はやんだが、それから紋所を三つ鱗にした。

.......................................................................

岐阜県 Gifu 池田町 Ikeda

yamanba 山姥 old woman in a mountain

山姥の危急を救ってやった男がいた。染物屋が紋付の着物を男のところにもってきたが覚えが無い。家紋に間違いが無いので受け取ったが、後日なくなっていた。山姥が持ち去ったのだといわれた。

.......................................................................

神奈川県 Kanagawa 小田原市 Odawara

hato 鳩 dove

小田原侯の御先手頭である山本源八郎の家紋は鳥居に鳩であるが、吉事がある前には鳩が集まるという。元は新御番という役目だったが、鳩が家に入ってくる度に出世していったという。

.......................................................................

鹿児島県 Kagoshima 伊佐郡 Isa district

Garappa, the Kappa ガラッパ / 河童

If people wear a robe with a family crest, put up a candle and look through the long sleeve of the kimono, they could see a Garappa.

.

Gataro ガタロ Kappa

If people went swimming in the river during the 祇園さん(天王さん Gion Festival, the Gataro would pull them in the water, so swimming was not allowed during that time.

The Shrine crest of the Gion shrine was a cucumber cut in slices, a favorite food of the Kappa. So during that festival people were not allowed to eat cucumbers.

祇園さんの神紋 Gion Shrine Crest

. Kappa Legends from Kyushu 河童伝説 - 九州 .

.......................................................................

宮城県 Miyagi 東松島市 Higashi Matsushima

kitsune 狐 the fox

Once upon a time

at a place called Ipponsugi 一本杉 (one cedar tree) a fox used to come out clad as a human in a 紋付羽織 haori coat with a family crest.

.......................................................................

島根県 Shimane 鹿島町 Kashima

ryuuja 竜蛇 dragon-serpent and shinmon 神紋 Shrine crest

佐太神社の西北にある恵曇(えとも)湾のイザナギ浜で竜蛇が上がった。板橋という社人が竜蛇上げを職掌としていた。今は恵曇や島根半島の漁師が9月末から11月にかけて沖合であげることが多い。竜蛇はサンダワラに神馬藻を敷いた上に乗せ、床の間に飾り、祝いをしたあと、佐太神社に奉納する。大きさは1尺2寸前後、背が黒く、原は黄色を帯びている。尾部に扇模様の神紋が見えると言われている。大漁、商売繁盛、火難・水難除けの守護神と信じられている。

.

神在祭の「お忌みさん」期間中、「お忌み荒れ」と言って海が非常に荒れる時がある。翌朝、1尺から1丈ほどの竜蛇が海岸に打ち上げられる。見つけた者は神社に奉納などする。竜蛇は竜宮からの使令で背には神紋があり、上がると豊年・豊漁だとされる。

.......................................................................

- source : nichibun yokai database -

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO . TOP . ]

- #tomoe #familycrest #kanibotan #kamon -

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Family Crest 家紋 kamon

Familienwappen

© PHOTO : yotchan

This is a

. Daruma from Shirakawa 白川だるま

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Mon (紋), also monshō (紋章) Monsho,

mondokoro (紋所), and kamon (家紋),

are Japanese emblems used to decorate and identify an individual or family. While mon is an encompassing term that may refer to any such device, kamon and mondokoro refer specifically to emblems used to identify a family.

The devices are similar to the badges and coats of arms in European heraldic tradition, which likewise are used to identify individuals and families. Mon are often referred to as crests in Western literature, which is another European heraldic device that approximates the mon in function.

On the battlefield, mon served as army standards, even though this usage was not universal and uniquely designed army standards were just as common as mon-based standards.

Check a long list of famous Japanese crests!

© More in the WIKIPEDIA !

.................................................................................

montsuki 紋付 formal wear with the family crest

CLICK for more photos !

monuwaeshi, mon uwa eshi 紋上絵師 painting family crests

The space for a family crest was usually left white by the cloth dyer and a special painter added the pattern and colors.

Since crests had become quite popular with the townspeople of Edo, they were used not only for official robes but also for decorations of every-day things, even 手ぬぐい tenugui hand towels.

The workshop of a crest painter did not take up much space and could be done in a small home in Edo.

- quote -

There are different styles of mon too. In the picture below, showing three variations of icho (ginko) mon, you can see three versions of a the mon: hinata – full sun (left), kage – shadow (middle), and nakakage – mid shadow (right). The more subtle versions are for slightly less formal occasions. There are also embroidered mon, called nui mon.

hinata mon 日向紋 - - - kage mon 陰紋 - - - nakakage mon 中陰紋

A family may choose a mon that is associated with their family (a family mon is called a kamon) or just opt for one they like instead. They are seen on all sorts of items in Japan: clothing, signs, boxes, ceramics, banners etc.

- source : wafuku.wordpress.com -

上絵の道具 tools of a crest painter

家紋を描くときに使う上絵道具の一部

(左から)from left to right

①分廻し(一本)bunmawashi compass to make a circle

②上絵筆(一本) ③定規 ④丸棒(二本) ⑤小刀(一本)

⑥丸刀(大、小) ⑦摺り込み刷毛(大,中、小) ⑧平刷毛(大、小)

⑨つや刷毛(大、中) ⑩平ゴテ ⑪丸ゴテ ⑫押さえゴテ

- Look at more photos how the tools are used:

- reference source : homepage2.nifty.com/montake/dougu -

「各種紋入れ加工」

「紋直し mon naoshi」「紋入れ・入れ紋 mon ire」「抜き紋 nuki mon」

「摺り込み紋 surikomi mon」「切り付け紋 kiritsuke mon 」

「のり落とし上絵 nori-otoshi uwa-e」「加賀紋 kaga mon」

(Kaga mon is a crest for a "fashionable person" and was very colorful, sometimes with embroidery.)

- with detailed descriptions

- reference source : homepage2.nifty.com/montake/eigyo -

- Check out the detailed page of 紋章上絵師

Itoo 伊藤武雄 Ito Takeo

- reference source : homepage2.nifty.com/montake/mon -

.......................................................................

. Edo craftsmen 江戸の職人 .

mongata shi 紋形師 craftsman making Mon patterns

source : edoichiba.jp.. mongata...

.......................................................................

- quote -

Family-crest master fears he’s one of a dying breed

- Tomoko Ontake - Japan Times -

Dressed in a black kimono and wearing a pair of eye-catching black, triple-framed spectacles, Shoryu Hatoba straightens his back as he sits on the tatami floor of his quaint studio in Ueno, central Tokyo, holding a pair of bamboo compasses fitted with a brush dipped in ink in place of a pencil.

- snip -

But 56-year-old Hatoba is now one of a dying breed of monshō uwae shi (family-crest painters and designers). “I’m an endangered species,” the Tokyo native concedes.

That’s because Japan is now on the verge of losing the tradition of making and preserving the ritual or everyday use of kamon (family crests) — which pretty much everyone in the nation once had. That’s despite the fact that its first known family crests date from the eighth century, when nobles at the Imperial court, and then samurai warriors, started using them as badges of identity or ownership.

But unlike in the West, where family crests were exclusively for the nobility, in Japan their adoption grew exponentially during the Edo Period (1603-1867), and especially during its economically and culturally vibrant golden age known as the Genroku era (1688-1704), Hatoba explains.

Then everyone, but men mostly, started featuring them in whatever design they liked on their kimono. That even included commoners — who mostly had no family names at all until a law in the modernizing Meiji Era (1868-1912) required everyone to have one — though Hatoba says women were generally late to the kamon party, only adopting them at the end of the Edo Period.

- snip -

The crests’ motifs are derived from a wide range of plants, birds and other animals.

- snip -

As a profession, monshō uwae shi demands microscopic attention to detail and command of many sophisticated techniques — not to mention aesthetic sensibilities. And, as Hatoba explains, a crest’s component parts all have to be rendered in a circular design on average only 38 mm in diameter for men’s kimono, and 21 mm for women’s. Interestingly, too, the number of crests on a kimono ranges from one to five — with more crests reflecting an occasion’s greater formality.

Hatoba, who apprenticed under a kamon craftsman for five years before opening his shop, is determined to keep the tradition alive. To do that, he has collaborated with creators and corporations in various genres, featuring kamon designs on everything from bags to boxes of wagashi (traditional Japanese) sweets.

- snip -

- source : Japan Times 2013 -

. Edo shokunin 江戸の職人 Edo craftsmen .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Some crests covered in the Daruma Museum

. Mitsuba Aoi 三つ葉葵 Hollycock of Tokugawa Clan

. Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康

. Tokugawa Mitsukuni 徳川 光圀

The famous inro box with the "mondokoro" from Mito Komon.

.................................................................................

. Asa no ha 麻の葉の家紋 Hemp leaf

. Kuyoo no mon, 九曜の紋

Nine planets, nine deities representing the stars

. Myooga 茗荷 Japanese Ginger

. Rindoo no mon 竜胆 gentian blossoms

. Rokumon sen 六文銭 Six coins of Sanada

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Daruma in a turtle shell crest

亀甲に達磨

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

More than 90 Crests from shrines and temples

shinmon 神紋 Shrine crest - jimon 寺紋 Temple crest

京都嵯峨清涼寺

source : secure.ne.jp/~x181007/kamon

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

- quote

A tomoe (巴), also 鞆絵, and tomowe (ともゑ) in its archaic form, is a Japanese abstract shape described as a swirl that resembles a comma or the usual form of a magatama. The origin of tomoe is uncertain. Some think that it originally meant tomoe (鞆絵), or drawings on tomo (鞆), a round arm protector used by an archer, whereas others see tomoe as stylized magatama.

It is a common design element in Japanese family emblems (家紋 kamon) and corporate logos, particularly in triplicate whorls known as mitsudomoe (三つ巴).

A mitsudomoe design on a taiko drum (note the negative space in the center forms a triskelion)

Some view the mitsudomoe as representative of the threefold division (Man, Earth, and Sky) at the heart of the Shinto religion. Originally, it was associated with the Shinto war deity Hachiman, and through that was adopted by the samurai as their traditional symbol. One mitsudomoe variant, the Hidari Gomon, is the traditional symbol of Okinawa.

The Koyasan Shingon sect of Buddhism uses the Hidari Gomon as a visual representation of the cycle of life.

© More in the WIKIPEDIA !

. Hachiman Shrines in the Edo period .

- quote

Okinawan Symbols and History of the Hidari-Gomon

The Hidari Gomon and it was once the Royal crest of Ryukyu Kingdom in Okinawa. In Japanese it is called the Hidari mitsudomoe and is a common design element in Japanese family emblems (家紋) and corporate logos. The Hidari Gonon is the primary traditional symbol of Okinawa. It is unclear who used the symbol first but it has special significance to the Okinawan people especially those practicing the ancient art of Okinawan Karate. I have heard a couple different interpretations of the meaning of the symbol so their may be more than one definition for the symbol.

The Koyasan Shingon sect of Buddhism which came from China to Japan uses the Hidari Gomon as a visual representation of the cycle of life. Others believe that the symbol is Shinto related because in Shinto mythology the symbol is often used to signify the structure taking place between three worlds. Such worlds include heaven, Earth, and the Underworld.

One explanation that was particularly interesting to me was the Okinawan folktale where they interpret the "Hidari Gomon" as representing loyalty, heroism, and altruism to a proud island people and their descendants. They believe it to be expressed through a past full of struggle and hardship, but also a willingness to face the difficulties the ahead no matter what the cost.

snip

Later, back in the Ryukyu Kingdom, the envoy described the death of three warriors to the King. The King after hearing the story of the Ryukyu guards deaths had up the Hidari-Gomon drawn up to symbolize their heroic action. The symbol is said to portray the three Ryukyu warriors spinning around in the pot giving their lives for the greater good of the people. The symbol has since become the symbol of the Ryukyu Kingdom, a symbol which can now be found just about everywhere in Okinawa.

Many Karate dojos have also incorporated its use into the symbols they use to represent their particular style of the ancient Okinawan art of Karate

- source : chicagookinawakenjinkai.blogspot.jp

.......................................................................

- quote -

tomoemon 巴文

1 - Also tomoe 巴. A pattern of one or more curled tadpole shapes inside a circle. The pattern is also called right tomoe, migidomoe 右巴, or left tomoe, hidaridomoe 左巴, depending on the direction in which the pattern curves. When the comma shapes are placed in opposite directions, the term kaeruko domoe 蛙子巴 is used. The expressions double tomoe, futatsudomoe 二つ巴, or triple tomoe, mitsudomoe 三つ巴 are used depending on the number of tadpole shapes used.

The pattern was used to decorate the eave-end semi-cylindrical tiles *nokidomoegawara 軒巴瓦, *nokimarugawara 軒丸瓦 on Buddhist temples.

The pattern first appeared in the Heian period and has continued to be popular to the present day. Sharp pointed tomoemon forms in the Heian period gradually changed to short rounded forms by the Edo period. The same is design is also found on roof-tiles in China, where the tomoemon is associated with water. Therefore, the tiles are believed to ward off fire. A tile with this design is known as *tomoegawara 巴瓦 or *hanamarugawara 端丸瓦.

2 -

A design pattern comprised of one or more spherical head-like shapes each with a connected curving tail-like shape which ends in a point. The character tomoe 巴 means eddy or whirlpool; however, it is not clear if this was the original idea of the design. Some scholars are convinced that it stems from the design on leather guard worn by ancient archers-tomo 鞆 thus tomo-e 鞆絵, a tomo picture.

Others say it was originally a representation of a coiled snake. It may be the oldest design in Japan, because it is similar in shape to the *magatama 曲玉 jewelry beads of the Yayoi period. It appears as a design on the wall paintings of the Byoudouin *Hououdou 平等院鳳凰堂 (1053) in Kyoto, and in the Illustrated Handscroll of the Tale of Genji Genji monogatari emaki 源氏物語絵巻 (early 12c). It was widely used from the Kamakura period onward and is often found on utensils, roof tiles and family and shrine heraldry. Its frequent appearance in connection with Shinto shrines indicates that it was thought to express the spirit of the gods. Patterns of one, two and three tomoe exist, some facing left, others right.

- source : JAANUS -

.......................................................................

kite with a tomoe 巴(ともえ)Tomoe pattern

. 静岡の凧 Kites from Shizuoka .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

CLICK for more photos !

kani botan, kani-botan 蟹牡丹 crab and peony

A crest where the blossoms and leaves of a peony are formed in a way to represent a crab.

It was often used for cloths and carpets.

. Kani Yakushi 蟹薬師 "Crab Yakushi" Temple .

Ochiai, Gifu

Sendai Botan 蟹牡丹(仙台牡丹)- Date clan

牡丹紋は延宝8年(1680)20世綱村が近衛家ら拝領、21世吉村は手を加えて蟹牡丹(仙台牡丹)としている。

鍋島緞通 carpet from Nabeshima

蟹牡丹唐草文 kani botan karakusa mon

Carpet with kani botan pattern.

- source : bunka.nii.ac.jp/heritages -

. karakusa 唐草 / からくさ Karakusa art motives .

karakusa moyoo 唐草模様 Karakusa pattern. Karakusa arabesque

Chinesischen Arabesken und Rankenornamente

.......................................................................

source : cocomiura3.cocolog-nifty.com

色絵牡丹文変形皿 kanibotan pattern - Nabeshima

鍋島

左右の葉が中央の牡丹の花を抱き込むように描かれています

蟹の姿を思わせるので”蟹牡丹”と呼ばれるそうです

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

. Legends and Tales from Japan 伝説 - Introduction .

kamon 家紋 family crest

If people fought about the parents of a child, in former times, they used to wash the 胞衣placenta in water and when it floated up, the proper Kamon would show.

.......................................................................

愛知県 Aichi 岩倉町 Iwakura

daija 大蛇 big serpent

じいさんが神社の裏を通りかかったとき、大蛇が這っていくのにでくわした。鳥肌が立って、3年間はこのことを口外しないので行ってくれと言うと、大蛇は去った。その大蛇は尾が切れていて、先のところに丸に太いと書いた文字がついていた。その字は神明様の御神紋だったので、大蛇は神明様のお使いと分かった。

.......................................................................

青森県 Aomori 大間町 Oma

hotoke no zaisho ホトケの罪障 Buddhist attonement for sins

Once a man about 38 years of age came to the temple asking what to do. He felt very weak and could not go to work any more. After some explanation this became clear:

In former times at this fisherman's home a dead body got caught in the net. The family had taken care of it in a funeral, but since the family crest was different, the man's sould could not go to the Buddhist paradise. So they performed a special ritual and he was healed.

.......................................................................

愛媛県 Ehime 成妙村 Narutaemura

shirohebi 白蛇 white serpent

昔、太宰家で紋付を出そうとしたが、櫃がどうしても開かない。櫃を叩き壊すと白蛇がいたので殺した。それからは、生まれる子みなに三つ鱗がついていた。太夫さんに祈祷してもらい怪異はやんだが、それから紋所を三つ鱗にした。

.......................................................................

岐阜県 Gifu 池田町 Ikeda

yamanba 山姥 old woman in a mountain

山姥の危急を救ってやった男がいた。染物屋が紋付の着物を男のところにもってきたが覚えが無い。家紋に間違いが無いので受け取ったが、後日なくなっていた。山姥が持ち去ったのだといわれた。

.......................................................................

神奈川県 Kanagawa 小田原市 Odawara

hato 鳩 dove

小田原侯の御先手頭である山本源八郎の家紋は鳥居に鳩であるが、吉事がある前には鳩が集まるという。元は新御番という役目だったが、鳩が家に入ってくる度に出世していったという。

.......................................................................

鹿児島県 Kagoshima 伊佐郡 Isa district

Garappa, the Kappa ガラッパ / 河童

If people wear a robe with a family crest, put up a candle and look through the long sleeve of the kimono, they could see a Garappa.

.

Gataro ガタロ Kappa

If people went swimming in the river during the 祇園さん(天王さん Gion Festival, the Gataro would pull them in the water, so swimming was not allowed during that time.

The Shrine crest of the Gion shrine was a cucumber cut in slices, a favorite food of the Kappa. So during that festival people were not allowed to eat cucumbers.

祇園さんの神紋 Gion Shrine Crest

. Kappa Legends from Kyushu 河童伝説 - 九州 .

.......................................................................

宮城県 Miyagi 東松島市 Higashi Matsushima

kitsune 狐 the fox

Once upon a time

at a place called Ipponsugi 一本杉 (one cedar tree) a fox used to come out clad as a human in a 紋付羽織 haori coat with a family crest.

.......................................................................

島根県 Shimane 鹿島町 Kashima

ryuuja 竜蛇 dragon-serpent and shinmon 神紋 Shrine crest

佐太神社の西北にある恵曇(えとも)湾のイザナギ浜で竜蛇が上がった。板橋という社人が竜蛇上げを職掌としていた。今は恵曇や島根半島の漁師が9月末から11月にかけて沖合であげることが多い。竜蛇はサンダワラに神馬藻を敷いた上に乗せ、床の間に飾り、祝いをしたあと、佐太神社に奉納する。大きさは1尺2寸前後、背が黒く、原は黄色を帯びている。尾部に扇模様の神紋が見えると言われている。大漁、商売繁盛、火難・水難除けの守護神と信じられている。

.

神在祭の「お忌みさん」期間中、「お忌み荒れ」と言って海が非常に荒れる時がある。翌朝、1尺から1丈ほどの竜蛇が海岸に打ち上げられる。見つけた者は神社に奉納などする。竜蛇は竜宮からの使令で背には神紋があり、上がると豊年・豊漁だとされる。

.......................................................................

- source : nichibun yokai database -

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO . TOP . ]

- #tomoe #familycrest #kanibotan #kamon -

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

12/07/2010

Harimi dustpan

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Paper dustpan はりみ harimi

Small dustpans made of strong washi paper.

They look almost like Daruma san himself.

Some are plain red, others feature a small picture, like a bird or the face of O-Kame.

The paper is made resistant with the extract of persimmons (kakishibu). They do not produce static electricity when used on tatami mats.

They are used with a soft broom to clean the tatami of traditional Japanese homes.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

chiritori ちりとり dustpan

chiritorinabe, chiritori nabe ちりとり鍋

Korean dish with a lot of kimchee

Hodgepodge with pork entrails.

. . . CLICK here for Photos !

. Reference .

.................................................................................

. Chami, cha mi - scoop for tea 茶箕(ちゃみ)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

mi み【箕】 winnow for grain

This was a most useful tool for the farmers of old, usually made at home in the winter months with material that grows around the house. It was used for fanning grains and carrying vegetables. Now there are many maschines to do the work and these MI are shown in museums of farmers tools.

observance kigo for mid-winter

mi matsuri 箕祭 (みまつり)

festival when putting the winnow away

..... mi osame 箕納(みおさめ)

kuwa osame 鍬納(くわおさめ)putting the hoe/plough away

This was done in a ritual with a feast just before the New Year.

箕祭や先祖代々小作農

mimatsuri ya senso daidai kosaku noo

winnow festival -

since ancestors generations we are

tenant farmers

Matsuda Daisei 松田大声

. Farmers work in all seasons - KIGO

.......................................................................

. Kobayashi Issa 小林一茶 .

背たけの箕をかぶる子やはつ時雨

seitake no mi o kaburu ko ya hatsu shigure

with a winnow the boy

covers his head...

first winter rain

Tr. David Lanoue

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

. Legends and Tales from Japan 伝説 - Introduction .

.......................................................................

Kagawa 香川県 長尾町 Nagao

oomino 大箕 the great winnow

On the first birthday of a baby there is a special ritual. The baby is presented with a kind of rucksack containing (誕生餅) special birthday mochi and a winnow with a book, an abacus, a pen, scisors, a ruler, a hammer or other things with the wish for a bright future as a craftsman.

. Soroban, Abacus 算盤、そろばん Abakus .

.......................................................................

Kochi, Nishi-Tosa 土佐

. shichinin misaki 七人ミサキ "Misaki of seven people" .

If someone gets ill, he has to stand at the entrance of the home, facing outside and the family members fan him with a 箕 winnow to make the illness go away.

- reference source : nichibun yokai database -

箕 61 legends to explore

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO . TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Paper dustpan はりみ harimi

Small dustpans made of strong washi paper.

They look almost like Daruma san himself.

Some are plain red, others feature a small picture, like a bird or the face of O-Kame.

The paper is made resistant with the extract of persimmons (kakishibu). They do not produce static electricity when used on tatami mats.

They are used with a soft broom to clean the tatami of traditional Japanese homes.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

chiritori ちりとり dustpan

chiritorinabe, chiritori nabe ちりとり鍋

Korean dish with a lot of kimchee

Hodgepodge with pork entrails.

. . . CLICK here for Photos !

. Reference .

.................................................................................

. Chami, cha mi - scoop for tea 茶箕(ちゃみ)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

mi み【箕】 winnow for grain

This was a most useful tool for the farmers of old, usually made at home in the winter months with material that grows around the house. It was used for fanning grains and carrying vegetables. Now there are many maschines to do the work and these MI are shown in museums of farmers tools.

observance kigo for mid-winter

mi matsuri 箕祭 (みまつり)

festival when putting the winnow away

..... mi osame 箕納(みおさめ)

kuwa osame 鍬納(くわおさめ)putting the hoe/plough away

This was done in a ritual with a feast just before the New Year.

箕祭や先祖代々小作農

mimatsuri ya senso daidai kosaku noo

winnow festival -

since ancestors generations we are

tenant farmers

Matsuda Daisei 松田大声

. Farmers work in all seasons - KIGO

.......................................................................

. Kobayashi Issa 小林一茶 .

背たけの箕をかぶる子やはつ時雨

seitake no mi o kaburu ko ya hatsu shigure

with a winnow the boy

covers his head...

first winter rain

Tr. David Lanoue

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

. Legends and Tales from Japan 伝説 - Introduction .

.......................................................................

Kagawa 香川県 長尾町 Nagao

oomino 大箕 the great winnow

On the first birthday of a baby there is a special ritual. The baby is presented with a kind of rucksack containing (誕生餅) special birthday mochi and a winnow with a book, an abacus, a pen, scisors, a ruler, a hammer or other things with the wish for a bright future as a craftsman.

. Soroban, Abacus 算盤、そろばん Abakus .

.......................................................................

Kochi, Nishi-Tosa 土佐

. shichinin misaki 七人ミサキ "Misaki of seven people" .

If someone gets ill, he has to stand at the entrance of the home, facing outside and the family members fan him with a 箕 winnow to make the illness go away.

- reference source : nichibun yokai database -

箕 61 legends to explore

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO . TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

7/24/2010

Nebuta Festival

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Nebuta Daruma Daishi - ねぶた達磨大師

ねぶたダルマ Neputa Festival, Nebuta Festival

Nebuta are illuminated floats which are paraded through the town in Aomori and other cities in Northern Japan.

The Nebuta Festival in Aomori is held in the beginning of August.

Face of Daruma

. . . Sources of the photos

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

quote

There are many theories about the origin of the Nebuta Festival. One is that it originated with the subjugation of rebels in the Aomori district by "General TAMURAMARO" in the early 800's. He had his army create large creatures, called "Nebuta", to frighten the enemy.

Another theory is that the Nebuta Festival was a development of the "TANABATA" festival in China. One of the customs during this festival was "TORO" floating. A "TORO" is a wooden frame box wrapped with Japanese paper. The Japanese light a candle inside the "TORO" and put it out to float on the river or the sea. The purpose for doing this is to purify themselves and send the evil spirits out to sea. "TORO" floating is still one of the most impressive and beautiful sights during the summer nights of the Japanese festivals. On the final night, "TORO" floating is accompanied by a large display of colorful fireworks. This is said to be the origin of the Nebuta Festival. Gradually these floats grew in size, as did the festivities, until they are the large size they are now.

Today the Nebuta floats are made of a wood base, carefully covered with this same Japanese paper, beautifully colored, and lighted from the inside with hundreds of light bulbs. In early August the colorful floats are pulled through the streets accompanied by people dancing in native Nebuta costumes, playing tunes on flutes and drums.

Many Aomori citizens are involved in the building of these beautiful floats. The Nebuta designers create their designs patterned after historical people or themes. They begin developing themes immediately after the previous year's festivities come to a close. Consequently, it takes the entire year, first in the development, then in the construction of the Nebuta float.

One of the reasons for the popularity of the Nebuta festival is that onlookers are invited and encouraged to participate. The sounds of the Nebuta drums and bamboo flutes inspire people to prepare costumes and begin practicing the Nebuta dances. As the beginning of the parade is signaled, "HANETO"(dancers) join hand-in-hand, and start their journey through the streets of Aomori. These dancers, colorfully arrayed in Nebuta garb, welcome audience participation. Feel free to join in a circle and enjoy the festivities!

We, the citizens of Aomori, would like to pass on this wonderful festival to our sons and daughters, in hope that it becomes a symbol of peace and hope to the coming generations.

source : Aomori Nebuta Excutive Committe

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

. nebutazuke ねぶたづけ/ ねぶた漬け

"Nebuta"-pickles

. Folk Toys from Aomori .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

The politician Fumio Ichinohe paints an eye for winning

to a Nebuta Daruma

source : www.ichinohefumio.jp/blog

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

An illuminated float (nebuta ねぶた) with

. Hachiroo and Nansoo-Boo

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

quote

Nemu no ki and the Nebuta Festival

In Japanese , NEMU NO KI ねむのき 合歓の木 is the name most commonly used for this tree, but in former days NEBU NO KI, NEBURI NO KI or NEMURI NO KI were used.

These all mean the same thing- THE SLEEPING TREE, when directly translated.

Now because of this SLEEP-LIKE behaviour, and its name ( formerly NEBU NO KI), the Japanese of old, used the leaves of this tree in a once common SUMMER RITUAL which was meant to drive away the SLEEPINESS ( NEMUKE 眠気) brought on by Japan`s hot season. This often took place on the morning of Tanabata ( the 7th day of the seventh month on the old calendar) and was called Nemuri Nagashi or NEBUTA NAGASHI ( literally- washing away sleepiness).

What happened was that when one woke up on the morning of the ritual, one rubbed the leaves of the nemu tree on ones eyes, symbolically wiping away fatigue. These same leaves were then tossed into a stream or river to be carried away, along with the bad energies which had been wiped away and absorbed.

Over theyears this ritual developed into much more elaborate summer festivals which were celebrated with the intention of reviving the people energies during th hot and LAZY season.

In many parts of North-Eastern Japan these festivals are still celebrated, with the most famous being the NEBUTA FESTIVAL of Aomori City. With tremendous crowds goig wild and its huge lanterns representing heroes of yore this festival is one of the great annual events IN THE WORLD.

source : blog.alientimes.org

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Das Nebuta-Fest

wird vom 2. bis 7. August in der Stadt Aomori gefeiert, der nördlichsten Großstadt auf der Hauptinsel Honshu. Es hat sich aus einem Tanabata-Sternenfest entwickelt und wird wie das Laternenfest in Akita entsprechend dem Mondkalender begangen.

Nebuta bedeutet „schläfrig sein“. Man wollte die müden Seelen aufwecken, weil die Ernte kurz vor der Tür stand. Eine andere Legende geht auf das 8. Jahrhundert zurück. Der General Tamura Maro soll mit derartigen Riesenlaternen die Feinde so erschreckt haben, dass er einen leichten Sieg errungen hat.

Die riesigen Laternen aus Bambus und Japanpapier werden auf Wagen montiert und in einer nächtlichen Parade durch die Stadt gezogen. Das Herstellen der Laternen nimmt die Bewohner der Stadt das ganze Jahr über in Anspruch; das Fest ist der Höhepunkt ihrer Bemühungen. Bis zu 50 Männer wechseln sich beim Ziehen eines Festwagens ab und die anfeuernden Rufe hallen von 17.30 Uhr bis 21.00 Uhr durch die Stadt. Zwischen den Laternen tanzen Frauengruppen in bunten Gewändern, hier können sogar Touristinnen mitmachen, wenn sie sich ein geeignetes Kostüm in einem Geschäft ausleihen.

Die Dekorationen auf den Laternen zeigen beliebte Figuren aus der Legende und Geschichte Japans, grimassenschneidende Kabuki-Schauspieler oder muskelstrotzende Kriegshelden. Sie werden mit dicken schwarzen Umrissen auf Papier gemalt und mit grellen Farben ausgepinselt. Am Abend kommen sie dann durch zahlreiche Lämpchen in ihrem Inneren zum Leben. Einige Handwerker der Stadt haben sich sogar auf die Herstellung der Nebuta-Laternen spezialisiert.

Die Parade zieht an jedem Festabend über 2,5 Kilometer durch die Innenstadt, wobei bis zu 20 Laternen vorgestellt werden. Am letzten Tag sind alle unterwegs und die Laterne mit der besten Dekoration wird gekürt: Sie darf auf einem Boot durch den Hafen von Aomori fahren, und ihre Hersteller sind die Helden des Tages.

Gabi Greve

August 2001

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

H A I K U

kigo for early autumn

nemurinagashi, nemuri nagashi 眠流し (ねむりながし)

..... nebuta 侫武多(ねぶた) Nebuta

. kingyo nebuta 金魚ねぶた(きんぎょねぶた)goldfish as nebuta toy .

oogidoro 扇燈籠(おぎどろ)"fan-shapet lantern"

kenka nebuta 喧嘩ねぶた(けんかねぶた)fighting nebuta floats

nemuta nagashi ねむた流し(ねむたながし)

onenburi おねんぶり

nebuta matsuri ねぶた祭(ねぶたまつり)Nebuta Festival

haneto 跳人(はねと) "jumping people"

dancers at the festival

They basically jump two times on the right foot and two times on the left, for about 2 hours during the long parade! This is not a dance, but a jumping performance.

. . . CLICK here for Photos !

. haneto ningyoo はねと人形 Haneto "jumping" dancer doll .

灯の入りて侫武多の武者の赤ら顔

hi no irete nebuta no musha no akara kao

when light is put in -

the red red faces of the

Nebuta warriours

Mimura Junya 三村純也 (1953 - )

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

. SAIJIKI ... OBSERVANCES, FESTIVALS

Kigo for Autumn

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO . TOP . ]

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Nebuta Daruma Daishi - ねぶた達磨大師

ねぶたダルマ Neputa Festival, Nebuta Festival

Nebuta are illuminated floats which are paraded through the town in Aomori and other cities in Northern Japan.

The Nebuta Festival in Aomori is held in the beginning of August.

Face of Daruma

. . . Sources of the photos

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

quote

There are many theories about the origin of the Nebuta Festival. One is that it originated with the subjugation of rebels in the Aomori district by "General TAMURAMARO" in the early 800's. He had his army create large creatures, called "Nebuta", to frighten the enemy.

Another theory is that the Nebuta Festival was a development of the "TANABATA" festival in China. One of the customs during this festival was "TORO" floating. A "TORO" is a wooden frame box wrapped with Japanese paper. The Japanese light a candle inside the "TORO" and put it out to float on the river or the sea. The purpose for doing this is to purify themselves and send the evil spirits out to sea. "TORO" floating is still one of the most impressive and beautiful sights during the summer nights of the Japanese festivals. On the final night, "TORO" floating is accompanied by a large display of colorful fireworks. This is said to be the origin of the Nebuta Festival. Gradually these floats grew in size, as did the festivities, until they are the large size they are now.

Today the Nebuta floats are made of a wood base, carefully covered with this same Japanese paper, beautifully colored, and lighted from the inside with hundreds of light bulbs. In early August the colorful floats are pulled through the streets accompanied by people dancing in native Nebuta costumes, playing tunes on flutes and drums.

Many Aomori citizens are involved in the building of these beautiful floats. The Nebuta designers create their designs patterned after historical people or themes. They begin developing themes immediately after the previous year's festivities come to a close. Consequently, it takes the entire year, first in the development, then in the construction of the Nebuta float.

One of the reasons for the popularity of the Nebuta festival is that onlookers are invited and encouraged to participate. The sounds of the Nebuta drums and bamboo flutes inspire people to prepare costumes and begin practicing the Nebuta dances. As the beginning of the parade is signaled, "HANETO"(dancers) join hand-in-hand, and start their journey through the streets of Aomori. These dancers, colorfully arrayed in Nebuta garb, welcome audience participation. Feel free to join in a circle and enjoy the festivities!

We, the citizens of Aomori, would like to pass on this wonderful festival to our sons and daughters, in hope that it becomes a symbol of peace and hope to the coming generations.

source : Aomori Nebuta Excutive Committe

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

. nebutazuke ねぶたづけ/ ねぶた漬け

"Nebuta"-pickles

. Folk Toys from Aomori .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

The politician Fumio Ichinohe paints an eye for winning

to a Nebuta Daruma

source : www.ichinohefumio.jp/blog

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

An illuminated float (nebuta ねぶた) with

. Hachiroo and Nansoo-Boo

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

quote

Nemu no ki and the Nebuta Festival

In Japanese , NEMU NO KI ねむのき 合歓の木 is the name most commonly used for this tree, but in former days NEBU NO KI, NEBURI NO KI or NEMURI NO KI were used.

These all mean the same thing- THE SLEEPING TREE, when directly translated.

Now because of this SLEEP-LIKE behaviour, and its name ( formerly NEBU NO KI), the Japanese of old, used the leaves of this tree in a once common SUMMER RITUAL which was meant to drive away the SLEEPINESS ( NEMUKE 眠気) brought on by Japan`s hot season. This often took place on the morning of Tanabata ( the 7th day of the seventh month on the old calendar) and was called Nemuri Nagashi or NEBUTA NAGASHI ( literally- washing away sleepiness).

What happened was that when one woke up on the morning of the ritual, one rubbed the leaves of the nemu tree on ones eyes, symbolically wiping away fatigue. These same leaves were then tossed into a stream or river to be carried away, along with the bad energies which had been wiped away and absorbed.

Over theyears this ritual developed into much more elaborate summer festivals which were celebrated with the intention of reviving the people energies during th hot and LAZY season.

In many parts of North-Eastern Japan these festivals are still celebrated, with the most famous being the NEBUTA FESTIVAL of Aomori City. With tremendous crowds goig wild and its huge lanterns representing heroes of yore this festival is one of the great annual events IN THE WORLD.

source : blog.alientimes.org

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Das Nebuta-Fest

wird vom 2. bis 7. August in der Stadt Aomori gefeiert, der nördlichsten Großstadt auf der Hauptinsel Honshu. Es hat sich aus einem Tanabata-Sternenfest entwickelt und wird wie das Laternenfest in Akita entsprechend dem Mondkalender begangen.

Nebuta bedeutet „schläfrig sein“. Man wollte die müden Seelen aufwecken, weil die Ernte kurz vor der Tür stand. Eine andere Legende geht auf das 8. Jahrhundert zurück. Der General Tamura Maro soll mit derartigen Riesenlaternen die Feinde so erschreckt haben, dass er einen leichten Sieg errungen hat.

Die riesigen Laternen aus Bambus und Japanpapier werden auf Wagen montiert und in einer nächtlichen Parade durch die Stadt gezogen. Das Herstellen der Laternen nimmt die Bewohner der Stadt das ganze Jahr über in Anspruch; das Fest ist der Höhepunkt ihrer Bemühungen. Bis zu 50 Männer wechseln sich beim Ziehen eines Festwagens ab und die anfeuernden Rufe hallen von 17.30 Uhr bis 21.00 Uhr durch die Stadt. Zwischen den Laternen tanzen Frauengruppen in bunten Gewändern, hier können sogar Touristinnen mitmachen, wenn sie sich ein geeignetes Kostüm in einem Geschäft ausleihen.

Die Dekorationen auf den Laternen zeigen beliebte Figuren aus der Legende und Geschichte Japans, grimassenschneidende Kabuki-Schauspieler oder muskelstrotzende Kriegshelden. Sie werden mit dicken schwarzen Umrissen auf Papier gemalt und mit grellen Farben ausgepinselt. Am Abend kommen sie dann durch zahlreiche Lämpchen in ihrem Inneren zum Leben. Einige Handwerker der Stadt haben sich sogar auf die Herstellung der Nebuta-Laternen spezialisiert.

Die Parade zieht an jedem Festabend über 2,5 Kilometer durch die Innenstadt, wobei bis zu 20 Laternen vorgestellt werden. Am letzten Tag sind alle unterwegs und die Laterne mit der besten Dekoration wird gekürt: Sie darf auf einem Boot durch den Hafen von Aomori fahren, und ihre Hersteller sind die Helden des Tages.

Gabi Greve

August 2001

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

H A I K U

kigo for early autumn

nemurinagashi, nemuri nagashi 眠流し (ねむりながし)

..... nebuta 侫武多(ねぶた) Nebuta

. kingyo nebuta 金魚ねぶた(きんぎょねぶた)goldfish as nebuta toy .

oogidoro 扇燈籠(おぎどろ)"fan-shapet lantern"

kenka nebuta 喧嘩ねぶた(けんかねぶた)fighting nebuta floats

nemuta nagashi ねむた流し(ねむたながし)

onenburi おねんぶり

nebuta matsuri ねぶた祭(ねぶたまつり)Nebuta Festival

haneto 跳人(はねと) "jumping people"

dancers at the festival

They basically jump two times on the right foot and two times on the left, for about 2 hours during the long parade! This is not a dance, but a jumping performance.

. . . CLICK here for Photos !

. haneto ningyoo はねと人形 Haneto "jumping" dancer doll .

灯の入りて侫武多の武者の赤ら顔

hi no irete nebuta no musha no akara kao

when light is put in -

the red red faces of the

Nebuta warriours

Mimura Junya 三村純也 (1953 - )

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

. SAIJIKI ... OBSERVANCES, FESTIVALS

Kigo for Autumn

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO . TOP . ]

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

7/11/2009

Red and Smallpox Essay

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

. akamono 赤物 "red things" amulets .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Hoosoogami, Hoosooshin

疱瘡神(ほうそうがみ、ほうそうしん)

Hosogami, the God of Smallpox

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

THE PATRIARCH WHO CAME FROM THE WEST

by Bernard Faure

Daruma, Smallpox and the color Red, the Double Life of a Patriarch

"La double vie du patriache", in Josef A. Kyburz et al., eds., Eloge des sources: Reflets du Japon ancien et moderne, Paris: Editions Philippe

Picquier, pp. 509-538.

Curtesy of Bernard Faure.

The footnotes are at the end.

Why did the patriarch Bodhidharma come from the West?

This is, of course, a famous kooan of Zen Buddhism, and Zen practitioners are supposed to find a non-intellectual answer reflecting the insight they have obtained through meditation. As to Bodhidharma, he has become a popular icon of Japanese culture and politics under the form of Daruma, the blind doll to the eyes of which one adds pupils to ensure the success of enterprises (for instance, in the modern period, on the evening of an electoral victory).

The Buddhist monk Bodhidharma (in Chinese Damo), an Indian missionary to China whom Christian missionaries long mistook for the apostle Thomas, was seen as an arhat and an avatar of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. As the founding patriach of the Chan/Zen school, he became eventually revered as an equal (and almost a double) of the Buddha himself. According to legend, Bodhidharma was the son of southern Indian king. Having obtained enlightenment, he left for China in order to convert the Chinese, and arrived in Canton at the beginning of the sixth century. His encounter with Emperor Liang Wudi (r. 502-49), a ruler who prided himself as a pious Buddhist, was a short one. Bodhidharma showed a certain lack of tactfulness when he declared that pious works were of no value. The emperor, not surprisingly, was annoyed by such bluntness and Bodhidharma deemed more prudent to leave right away for North China. Legend has it that he crossed the Yangze River on a reed, an element which made its way into iconography and to which I will return.

He settled on Song shan, where he is said to have practiced meditation during nine years facing a wall — another element to which I will return. Bodhidharma’s lofty teaching won him a few disciples, but also some powerful enemies, and we are told that he was eventually poisoned by two rivals. Soon after his death, however, a Chinese emissary returning from India claimed to have met him on the Pamir plateau. When Bodhidharma’s tomb was opened, it was found empty. It was therefore concluded that he was a sort of Daoist Immortal, and that his death was only a feigned death. This is, in a nutshell, the legend as it developed within the Chan/Zen tradition.

Such is, in its outline, the image of Bodhidharma as it developed in the Chan tradition toward the eighth century. The legend of the Indian patriarch, however, continued to develop outside of Buddhism, as shown by the attribution to this master of several Daoist works, as well as his promotion to the rank of founder of martial arts.[1] If the Bodhidharma worshiped as the first patriarch of Chan in China as little to do with the Indian monk of the same name, who was mentioned as admiring the pagoda of the Yongning Monastery in Luoyang at the beginning of the sixth century, the distance between the Japanese Daruma and his Chinese prototype seems even greater.

According to a later Japanese tradition, Bodhidharma did not return to India but traveled on to Japan. This version, propagated by the Tendai school, associates Bodhidharma with Shootoku Taishi, who came himself to be considered an avatar of the Tiantai master Nanyue Huisi (517-77). We are told that Shootoku Taishi one day met a starving beggar at the foot of Mt Kataoka (in Nara Prefecture) and exchanged a poem with him. The strange literate beggar was first identified as an immortal in the Nihon shoki. His further identification with Bodhidharma rested upon another widespread legend, according to which Huisi had once been Bodhidharma’s disciple. When the two first met on Mount Tiantai, Bodhidharma predicted that they would both meet again in a next life in Japan. This legend grew with the cult of Shootoku Taishi in the medieval period, and there is still a Daruma Temple at Kataoka, not far from Horyuuji — a monastery associated with Shootoku Taishi.

Let us leap ten centuries forward. Daruma became an extremely popular deity during the Edo period as a protector of children and bringer of good luck. In this folkloric version, the Indian patriarch of Chan/Zen has come a long way. He has been represented since that time as a legless, tumbling talisman doll, which, as the saying goes, “falls seven times and rises eight times." (nana korobi ya oki).[2] This popular representation of Daruma traces its origin back to the belief according to which Bodhidharma, after sitting in meditation for nine years in a cave on Song shan, came to lose his legs.