:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Sake, Ricewine and Daruma

Nihonshuu, 日本酒, the Drink of Japan

quote

Anyone who has ever been to Japan has probably fallen under the spell of a soothing cup of sake at one time or another. An encounter with Japan's favorite libation is bound to be memorable.....

In a land where so much real business takes place off the record, sake is the oil that keeps the wheels of society turning smoothly.

The Buddhist version of Sake is called

the Water of Wisdom, Hanya no Mizu, 般若の水,

and consumed even by monks and priests at prestigeous temple compounds.

source : The Insider's Guide to Sake

Philip Harper

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

quote

The Origin of Sake

Wet rice cultivation started in Japan nearly 2,500 years ago, and the production of sake seems to have come with it. Initially, it was produced by chewing up and spitting rice into a large bowl to ferment. This "kuchikami" sake was replaced many centuries later with the discovery of yeast, which also increased the alcoholic content.

Sake also had an important social function. Drinking sake brings the gods among people, assisting them to cooperate and live together, easing relationships within the community. For this reason, sake was not usually drunk alone, but with others. It is also always placed on the grave of dead relatives along with an item of food.

Different types of Sake

Sake is traditionally served hot in the winter from a small earthen-ware bottles (tokkuri) and cups (sakazuki), but special kinds of sake are now brewed for drinking cold or on ice as desired. The varieties of sake are determined by the quality of ingredients used and standards set by law. The three main types of sake are:

Ginjo-shu (吟醸酒)

Premium sake made from choice ingredients where rice is not polished to more than 60% of its weight-using the pure starch center of the grain. The enhanced aromatic fragrance and potent flavour can resemble the taste of some western wines and is consumed mainly with sashimi or as an after-dinner drink.

Junmai-shu (純米酒)

A 'pure' sake brewed from only water and koji rice which is not polished by more than 70%. Its features are the distinctively full-bodied flavour and aroma, and is most commonly served in izakaya bars.

Honjozo-shu (本醸造酒)

Used with the same ingredients as Junmaishu yet has brewing alcohol added to help produce a mild taste and fragrant aroma. When mixed with Ginjoshu, the resulting sake is known to be the most delicious, refined and expensive of all.

quote : www.pref. saga.jp

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

- source : imayo tsukasa Niigata -

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

- quote -

miki お神酒 Shinshu

Rice wine (sake) offered to the kami, a necessary part of the food offerings known as shinsen. Usually referred to as omiki, or alternately as shinshu, the term miki is a combination of two characters, the honorific mi and the character for "wine" (ki).

As such, it originally derived from a term for wine offered to someone in an exalted position. In ancient documents, miki is also called miwa, and the deity Miwa no kami is thus famous as the kami who presides over sake.

Likewise, the term kushi is found in the songs of the Kojiki as another name for miki, while in Okinawa, one still finds the term ugusu. This word is thought to derive from the ancient view of the "auspicious" (kizui) effect of sake, while another theory links the word to kusuri or "medicine."

All these examples demonstrate that miki has been considered essential to kami worship from legendary times until the present. It is believed that by drinking miki together with the kami to whom it is offered, the celebrants can deepen their communion with the kami. by reaching a state of mind and body not normally experienced in everyday life.

Thus, the meaning of miki is explained as referring to deepening exchange with the kami. There are numerous varieties of miki, including white rice wine and black rice wine (shiroki and kuroki), unrefined rice wine (nigorizake), refined rice wine (sumisake or seishu), and sweet rice wine (hitoyozake).

Likewise, there are several methods of brewing.

Examples the ancient period include a strong "wine of eight-fold brewing" (yashioori no sake), and another "overnight" type of wine called reishu, which ferments when chewed. The ritual offerings of certain localities feature kinds of miki that are so thick they can be picked up with chopsticks.

- source : Saito Michiko, kokugakuin

The religious use of sake, (o-miki お神酒)

In the word o-miki, the reading "ki" is assigned to the character for sake. As such, the final meaning would again be akin to "the sake that helps one prosper," but perhaps this time there is a bit more of a religious association. Linguistically, sakae-no-ki changed to sakae-no-ke, sakae-ke and sake-ke before arriving at the vernacular manifestation we use today.

source : JOHN GAUNTNER

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

I have written extensively about

Tokkuri - Drinking Hot Sake with Daruma 徳利とだるま

BACKUP TEXT only

Sakazuki - Small cups to drink Sake 杯 とだるま

Sakadaru 酒樽 sake barrel, sake cask and wooden masu 升 cups

Sake Matsuri 酒祭 Sake festival in November

Shrine Hibita Jinja 比々多神社, Isehara, Kanagawa

. WKD : Ricewine, rice wine (sake, saké, saki 酒) .

and related KIGO

Jizake 地酒 local ricewine brands

My Photoalbum about Sake and Daruma

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

THE BOOK OF SAKE

Book Review

© ROBBIE SWINNERTON, The Japan Times, December 2006

A Connoisseur's Guide, by Philip Harper.

Kodansha International, 2006, 96 pp.

How the global culinary pendulum does swing. It was not so long ago that drinking sake was considered as exotic, or even as ill advised, as eating raw fish seasoned with green horseradish. Now, with sushi an international fad, Japan's traditional tipple is also starting to make serious inroads onto dining tables around the world.

However, even as misperceptions about sake are cleared up -- that it is not a spirit akin to vodka; that it is not always drunk hot out of thimble-size cups; that it does not necessarily cause hangovers that feel like being thumped by a sumo wrestler -- there are still many barriers holding it back from gaining more widespread acceptance.

As with wine -- with which, fairly or otherwise, it must be compared -- sake comes in a daunting array of labels and with a bewildering vocabulary. Unlike wine, though, there are fewer clues to help break through the ignorance barrier. Sake does not come in two readily identifiable colors (red or white), with clearly defined varietals (such as Chardonnay or Merlot) that give clues about its flavor and character.

But the biggest hindrance to understanding sake is that there is still not enough written (in English, at any rate) on the subject. Sake is a foreign country and we need good guidebooks to help us to find our way, pointing out both the highlights and the areas to avoid, with clear, concise translations of essential phrases.

Few people are better qualified to show us around than Philip Harper. Not only was he the first Westerner to join the workforce of a kura (sake brewery), he is the only foreigner ever to reach the exalted rank of toji (brewmaster). But it is not just his accomplishment in breaking into such an arcane world that makes Harper such a good guide. After 15 years in the business, he is just as enthusiastic about his calling as when he started. Not only does he still remember his first sips of sake, he understands that to appreciate this heady brew we do not need to know the history and jargon. We just need to open a bottle (or two) and start drinking.

That is why his lavishly illustrated new book, most aptly subtitled "A Connoisseur's Guide," starts out with fundamentals. Which kinds of sake should be chilled before being served? Which are better heated? As Harper writes, "there are persuasive reasons to enjoy sake at all temperatures [but] finding the sweet spot for the particular sake you are drinking will double your pleasure."

He also tackles the question of pairing sake with food. Obviously, sake goes brilliantly with Japanese cuisine -- indeed premium ginjo sake served with fine sashimi is one of those sublime matches made in culinary heaven. More robust brews are called for when sitting down to sukiyaki or nibbling on yakitori. Tempura, he suggests, is well suited to a juicy junmai or a flavorful yamahai.

We must acquaint ourselves with terminology of this kind if we are to become connoisseurs (just as a wine drinker needs to know the difference between Sauvignon and Shiraz). Harper introduces the various styles of sake early on, describing the wide spectrum of flavors they offer, but without getting too technical too fast.

He tells us what makes the best aperitif (perhaps a deluxe dai-ginjo) or post-prandial snifter (a rich, well-aged koshu, which he compares to brandy, although it is far closer in nature to amontillado or Pedro Ximenes sherry). He also encourages us to try sake with Chinese or Western cuisine, and even with curries.

Having whetted our appetites -- quite literally, as it is hard to dip into this book without wanting to open a bottle and sip as we read -- Harper draws us into the more rarefied world of sake tasting, introducing an English version of the Sake Flavor Chart developed by sake authority Haruo Matsuzaki. He also explains that the label on your bottle is more than just beautiful (but so inscrutable) calligraphy. It gives useful information that can help you select your brew, and even without knowledge of kanji there are plenty of clues to be deciphered.

But for the would-be connoisseur, it is the second half of the book that is most useful. The differences in the taste of sake derive from regional variations in climate and culture, the various types of rice used in the brewing process and the influence of the brewing guilds. Harper describes these in language that is always clear to the lay reader.

He makes this information practical by including reviews (translated from Matsuzaki's original Japanese) of some 50 different brews from all over Japan. We are given specific names and labels to look out for, along with a run-down of the flavor profiles and brief descriptions of each brewery. Further historical and cultural snippets are inserted via sidebars and boxes dealing with arcana such as the meanings of sake names or how a strain of sake yeast was developed.

© ROBBIE SWINNERTON, The Japan Times, December 2006

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

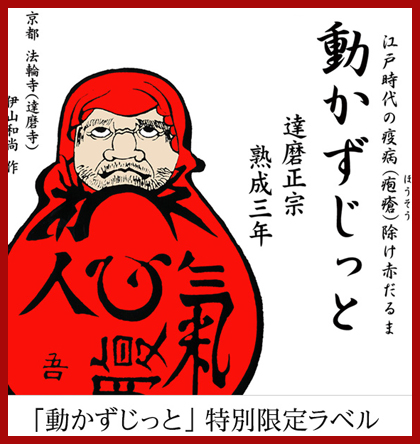

- reference source : daruma-masamune.co.jp... -

Advertising Daruma Sake

This is a present for a politician who has won an election. He can then paint the second eye into the face, open the barrel of ricewine and start celebrating with his friends !

© PHOTO : nanyo brewery

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

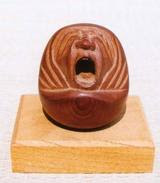

Tokkuri, Sake Pourers with two laughing Daruma

Quote:

What a face! Unable to contain himself on one tokkuri, Daruma blasts out with a hearty laugh that one can almost hear on the other. On the base is written 'Heian, Jyuzan' which means it was made in Kyoto by one Jyuzan or Long-life mountain. Holding a brush-like 'duster' in his right hand, possibly to swat the mosquito that hovers on the back of this whimsical pair, Daruma has been painted with lively

animation.

Meiji period, 14.8cm.tall and 6.5cm.across, square form, no box.

http://www.trocadero.com/japanesepottery/

Photo is here !

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Sake World Com. John Gauntner

The Best Online Information !

Ode to Japanese Pottery: Sake Cups and Flasks

by Robert Yellin

http://www.japanesepottery.com/Site_Map/book-yellin/book-yellin.html

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

SCHNAPS shoochuu shochu 焼酎

A brand from Hiroshima

Made from sweet potatoes

広島ならではの地元にこだわった本格芋焼酎に挑戦しました

25度 達磨 黒麹(紅あずま)720ml瓶

© 中国醸造 広島県

Apron 前掛け maekake

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

酒甕に蓋して守るや麦嵐

sakagame ni futa shite moru ya mugi-arashi

for the sake pot

a cover to protect it -

storm on the barley

Yasui Kooji 安井浩司 Yasui Koji

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO TOP . ]

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

3 comments:

Japan Times, Feb. 19, 2008

http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/ek20080219wh.html

By ALICE GORDENKER

Dear Alice,

Recently, while conducting some, uh, research into Japanese alcoholic beverages, I was surprised to notice that the alcohol content of canned chuhai cocktails varies significantly by flavor. The grape-flavored chuhai I was imbibing contained 5 percent alcohol, while the lemon version of the same brand packed appreciably more punch at 7 percent. What the heck is that? And while you 're at it, what the heck is a chuhai? The nomenclature seems to cover a huge range of drinks, but darned if I know what's in 'em.

Randall E., Tokyo

Dear Randall,

I must confess that I myself have never partaken of the pleasures of chuhai, being a strictly beer-wine-sake-whiskey-and-oh-don't- forget-champagne kind of gal. But in the spirit of, uh, research, I headed over to my local convenience store and ventured into unknown aisles. And you're right — the charge in chuhai products varies from 4 to 7 percent alcohol.

Before we go into why, I should explain that the word chuhai is one of those colloquial contractions that takes a two-word phrase — usually including one or more loan words from English — and chops it down into something shorter and snappier.

Examples are rimokon for remote control and sekuhara for sexual harassment. In a similar fashion, chuhai was created with the second syllable of the Japanese word shochu and the first syllable of the English word highball, as in the cocktail.

Chuhai, which you also see written in roman letters as chuhi and chu-hi, is a mixed drink that appeared shortly after World War II, when alcohol was in short supply. Whiskey was truly a luxury, and most drinkers had to settle for shochu, an inexpensive spirit that can be distilled from just about anything you might have lying around your kitchen.

Sweet potatoes are common as the base ingredient, but the legal definition permits the use of wheat, barley, brown sugar, buckwheat, sesame, chestnuts and even milk. Shochu can also be made from rice, but the process is different from that used to make sake and the finished product comes out stronger and less fruity.

In the last five or so years, shochu has gotten trendy and is often of high quality. But in the chaotic postwar period it was usually foul-tasting hooch of dubious origin.

To make it go down easier, the street stalls and saloons that served it started mixing it with soda water and calling it a "shochu highball," or chuhai, for short. The concoction spread quickly, with variations made by adding fruit juice, flavored syrup or tea.

The first ready-to-drink chuhai product to retail in stores (rather than bars) was released in 1983 by a company called Toyo Shuzo, with the catchy brand name of "hiLicky." (Later, the company merged with Asahi Kasei and the can now reads "hiLiki.") It was a big hit with young people, and the success of the product encouraged other manufacturers to enter the market with their own canned and bottled versions.

These days, chuhai has matured into a 600,000 kiloliters per year product, which, if my calculations are correct, means Japanese consumers are knocking back 1.7 billion cans every year. That 's still less than a tenth of the beer market, but chuhai is gaining steadily. Among women in their 20s, chuhai has elbowed aside beer as the preferred drink.

The beautiful irony here is that the best-selling canned chuhai, Kirin's Hyoketsu brand, isn 't even made with shochu, but vodka. Nevertheless, I took your question over to Kirin because I figured the market leader ought to know a thing or two about chuhai. Brand manager Kunihiko Kadota assured me that canned cocktails made with vodka and wine are just as much chuhai as those made with shochu, and explained that there are two reasons why alcohol content varies by flavor.

"The first, and most important reason, is taste," Kadota told me. "Strong citrus flavors like lemon and grapefruit, which are the two most popular flavors for all chuhai drinks, go very well with alcohol and seem to demand a higher alcohol content for good balance," Kadota said. "We do make citrus flavors with lower alcohol content, but most drinkers, and men in particular, prefer the higher alcohol versions.

"On the other hand, what we call 'soft-fruit' flavors, including grape, apple and peach, are less assertive and can't handle 6 or 7 percent alcohol," he explained. "Those drinks would taste too strong with that much alcohol. And customers who gravitate to these flavors, usually women, prefer a drink they won't feel as fast. So that's the other reason we vary the alcohol content of products in our brand: to satisfy consumers who want a less alcoholic drink as well as those who want a drink with more kick."

If you want a really high-octane chuhai, you'll have to make your own. A canned or bottled product with 9 percent alcohol or higher is subject to a higher tax. That's something manufacturers want to avoid, because part of the appeal of chuhai is its relative low cost. A 350-ml can retails for ¥140-150, compared to roughly ¥160 for happoshu (low-malt beer-like beverages) and ¥220 for beer. The main reason for the price differential is tax; beer has the highest rate among the three.

If you'd like to do some more, uh, research, how about going in search of an authentic old-time chuhai as they were made in the immediate postwar period? Though lots of bars offer what's called a ganso (original) chuhai, why not head straight to the source — the area in eastern Tokyo along the Keisei train lines, which is supposedly where chuhai originated?

A good place to start might be Sanyu Sakaba (Yahiro 2-2-12, Sumida-ku; [03] 3610-0793) near Keisei Hikibune Station on the Keisei Line. It's one of three or four drinking dens that claim to have invented the chuhai.

Matsunoo Taisha 松尾大社 Matsunoo Grand Shrine

Matsuno'o Taisha

and

sake brewing

.

Sake 酒 for rituals and festivals

.

http://japanshrinestemples.blogspot.jp/2015/04/sake-rituals-festivals.html

.

Post a Comment